Jeffrey Grospe

Last month I wrote about the practice of walking meditation and how this daily activity, or something similar, can be woven into one’s regular mindfulness practice. In this month’s article, I’ll expand on my explanation of walking meditation by presenting some variations you might want to try to incorporate into your own practice.

First, it can make sense to try linking your breathing to your walking. Naturally, one’s out-breath is longer than the in-breath. So perhaps you’ll find it easeful to take two steps per in-breath and three per out-breath, or three steps per in-breath, and four steps per out-breath. I encourage you to bring some curiosity and play into the mix as you find a pattern that works for you, being careful to match your steps to your breath, rather than the other way around. What do you notice?

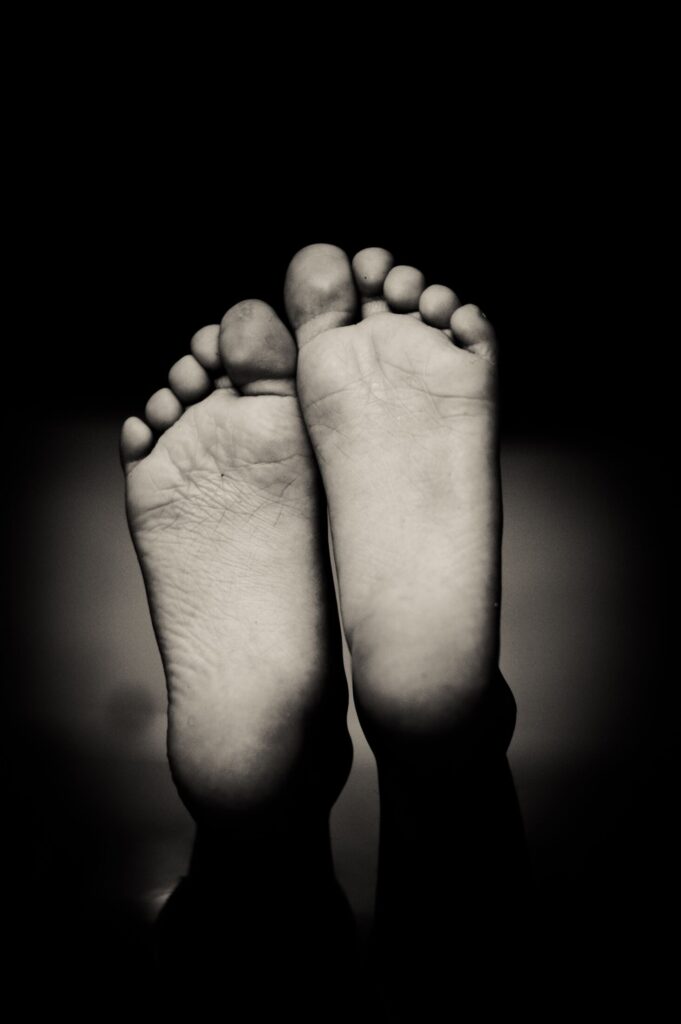

For some of us, our movement practice involves regular motions with our arms or legs that are different than the walking stride. If you don’t practice walking meditation, perhaps you knead your feet on the floor or bed or squeeze your hands as a regular movement practice. In these cases, the breath can be linked to the rhythm of these movements in a very similar fashion. How many in-breaths does your full motion take? How many out-breaths? Allow your creativity to come through and see what works for you this time…and next time.

Danie Franco

Second, it can also be helpful to anchor your awareness to words or phrases that pair with each of your footsteps or body movements. For example, one way to describe the foot movement in the walking sequence could be like this:

Lifting the stepping foot – Lift

Swinging the foot forward – Swing

Placing the stepping foot on the ground – Place

Shifting weight onto the stepping foot – Shift

These same movements would then be repeated with the next leg, using the same word cues: Lift, Swing, Place, Shift (or feel free to use words you find more suitable).

Or it could be that a rhythmic movement of your hands works best for your body. If this is true for you, one idea could be:

Grasp the arm of your chair with your left hand – Grasp

Squeeze the arm of your chair with your left hand – Squeeze

Grasp the arm of your chair with your right hand – Grasp

Squeeze the arm of the arm of your chair with your right hand – Squeeze

These same word cues of Grasp, Squeeze can be repeated as many times as you would like to perform this particular practice. How many repetitions feel right to you? Is there any other way you can tweak the practice to fit your body or your style a little bit more?

Brett Jordan

Next, anchoring phrases, sometimes used while sitting, can be applied to walking or other rhythmic body movements like this one from the late Zen master, Thich Nhat Hanh. As you say each phrase, the invitation is to either take a step or perform the next rhythmic movement of a foot, hand, or arm that works for your body:

I have arrived.I am home.In the here.In the now.

Or you can simplify these phrases into single words that pair with each range of motion: Arrived. Home. Here. Now.

As Thich Nhat Hanh said in his book, How to Walk (2014):

“We can practice mindfulness in every moment of the day as we walk from one place to another. When we walk through a door, we know that we are going through a door. Our minds are with our actions,” (page 12).

When contemplating this quote, we can also expand its meaning by replacing the word “walk” with “move”, which incorporates all forms of transport. How would you describe your ‘mind being with your actions’ when you do walking or movement practice?

Sebastien Goldberg

Finally, consider how walking meditation, or paying attention to deliberate movement, can bring joy to and increased awareness of the beauty around us. For example, on a hike this past summer, I found myself struggling with a steep uphill climb and fixating on how much further I had to travel before getting to my “destination”, not really noticing the beauty all around me. At one point I stopped for a drink of water and to catch my breath. The pause opened my eyes: I was in a quintessentially beautiful sun-streaked Pacific Northwest forest with moss draped logs and salal. Around me stood both towering and baby hemlock trees. And all these sights and smells were drenched in the sound of a cascading river. I waited for my heart rate to settle before moving on, more slowly, more mindfully. I was here not to get to the campsite, but to enjoy these woods. Thereafter, I stopped often to savor my surroundings.

Another Thich Nhat Hanh quote speaks to this, too:

“In every one of us there’s a tendency to run. There’s a belief that happiness is not possible here and now, so we have the tendency to run into the future in order to look for happiness…Walking brings the mind and body together. Only when mind and body are united are we truly in the here and the now. When we walk, we come home to ourselves,” (page 24).

In one way or another, we are all moving into the future. If we do so mindfully, we bring our mind and our body together. And as we bring greater awareness into the rhythmic movements of our stride or another body part in varying ways, may we, too, come home to ourselves a little bit more.

Beth Glosten, M.D., is an instructor with Mindfulness Northwest.

This article was part of our Practice Letter newsletter. If you’d like to receive this monthly publication in your Inbox, please sign up here.