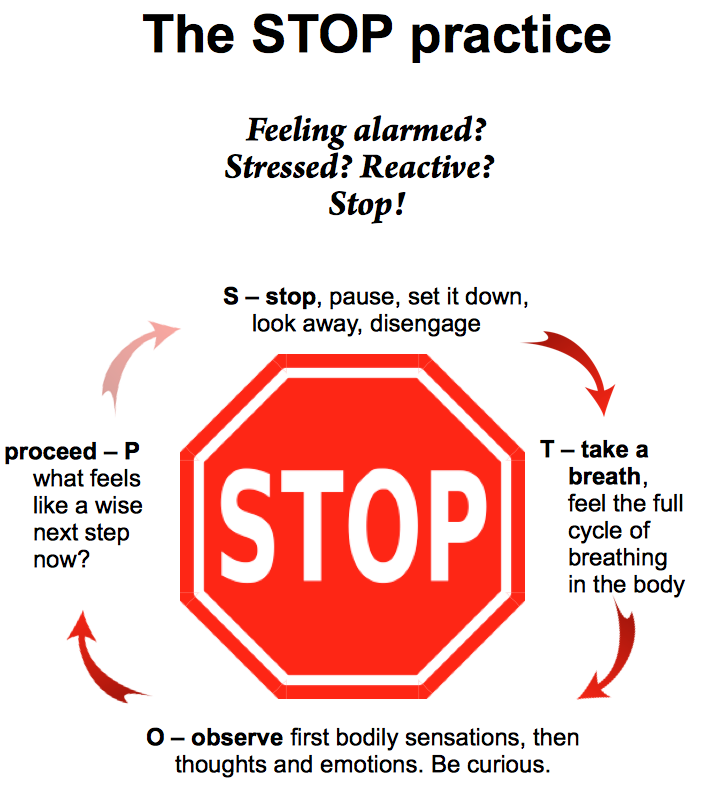

Feeling alarmed? Getting reactive? Try STOP-ing. By helping you drop below the “story line” and into your lived experience, this brief practice may help you feel the space between stimulus and response. At the very least, it may prevent you from doing or saying something you’ll regret.

Graphic by Tim Burnett, (c) Mindfulness Northwest, 2012

Stress got you down? Try this tip to balance throughout the day

By ELISHA GOLDSTEIN, PH.D.

I often say that there are two things we can count on in this life besides death and taxes and that is stress and pain. Two thirds of Americans claim that they are likely to seek help for stress (American Psychological Association) and over 19 million Americans alone suffer from some form of anxiety. While this may seem like depressing statistics, it’s important to know and acknowledge the facts. When we know what the issues are, we can work toward a plan to alleviate then which cultivates the strength of hope.

However, it’s important to clarify that the problem isn’t stress. The problem is how we relate to the stress. Let me briefly lay the foundation for how a stress reaction works. Back in the day when we used to experience life-threatening situations (e.g., getting chased by a tiger), our blood got redirected to our muscles as our bodies got geared up to either fight or flee for the situation. This stress response is critical to our survival. It can save our lives or enable a firefighter to carry a 300-pound man down twenty flights of stairs. However, most of us don’t face these type of threats very often today, but instead a stress reaction is often created in response to a thought, emotion or physical sensation we have. If we’re actively worried about whether we’re going to be able to put food on the table or not getting the perfect score on the next exam, this reaction will be activated. If these systems don’t slow down and normalize, the effects can become disastrous and we can succumb to a variety of ailments including high blood pressure, muscle tension, anxiety, insomnia, gastro-digestive complaints, and a suppressed immune system which compromises the ability to fight disease.

So what can you do?

Creating space to come down from the worried mind and back into the present moment has been shown to be enormously helpful to people. When we are present we have a firmer grasp of all our options and resources which often make us feel better. Next time you find your mind racing with stress, try the acronym S.T.O.P.:

S – Stop what you are doing, put things down for a minute.

T – Take a breath. Breathe normally and naturally and follow your breath coming in and of your nose. You can even say to yourself “in” as you’re breathing in and “out” as you’re breathing out if that helps with concentration.

O – Observe your thoughts, feelings, and emotions. You can reflect about what is on your mind and also notice that thoughts are not facts and they are not permanent. If the thought arises that you are inadequate, just notice the thought, let it be, and continue on. Notice any emotions that are there and just name them. Recent research out of UCLA says that just naming your emotions can have a calming effect. Then notice your body. Are you standing or sitting? How is your posture? Any aches and pains.

P – Proceed with something that will support you in the moment. Whether that is talking to a friend or just rubbing your shoulders.

Many people who I discuss this with like to put this in their electronic calendars for a couple times a day and practice it even when they’re not stressed to get the feel for it so they can better remember to access it when they are stressed.

From PscyhCentral Online: Mindfulness & Psychology see also Elisha Goldstein’s The Now Effect